How To Solve A Word Problem Involving Free Throws, Two Point Field Goals And Three Point Field Goals

fourteen.3 Problem Solving and Conclusion Making in Groups

Learning Objectives

- Discuss the common components and characteristics of problems.

- Explain the five steps of the group problem-solving procedure.

- Depict the brainstorming and discussion that should have place before the group makes a determination.

- Compare and contrast the unlike decision-making techniques.

- Discuss the diverse influences on decision making.

Although the steps of problem solving and decision making that we will discuss side by side may seem obvious, we often don't think to or choose not to apply them. Instead, we start working on a problem and later realize we are lost and have to backtrack. I'm sure we've all reached a bespeak in a project or task and had the "OK, now what?" moment. I've recently taken up some carpentry projects as a functional hobby, and I take developed a great respect for the importance of avant-garde planning. It'south frustrating to get to a crucial point in building or fixing something but to realize that you take to unscrew a back up lath that you lot already screwed in, have to drive back to the hardware shop to get something that you didn't remember to go earlier, or have to completely showtime over. In this department, we will discuss the group problem-solving process, methods of decision making, and influences on these processes.

Group Trouble Solving

The problem-solving process involves thoughts, discussions, actions, and decisions that occur from the kickoff consideration of a problematic situation to the goal. The problems that groups face are varied, just some common problems include budgeting funds, raising funds, planning events, addressing customer or denizen complaints, creating or adapting products or services to fit needs, supporting members, and raising awareness most problems or causes.

Problems of all sorts take 3 mutual components (Adams & Galanes, 2009):

- An undesirable situation. When weather condition are desirable, at that place isn't a problem.

- A desired situation. Even though information technology may but exist a vague idea, there is a drive to amend the undesirable situation. The vague thought may develop into a more than precise goal that can be achieved, although solutions are not yet generated.

- Obstacles between undesirable and desirable situation. These are things that stand in the way between the electric current situation and the group's goal of addressing it. This component of a problem requires the most piece of work, and it is the part where conclusion making occurs. Some examples of obstacles include express funding, resources, personnel, time, or information. Obstacles can also accept the course of people who are working against the grouping, including people resistant to change or people who disagree.

Discussion of these three elements of a trouble helps the group tailor its problem-solving process, as each problem will vary. While these three general elements are nowadays in each problem, the group should too address specific characteristics of the problem. V common and important characteristics to consider are task difficulty, number of possible solutions, grouping member interest in problem, group fellow member familiarity with trouble, and the demand for solution acceptance (Adams & Galanes, 2009).

- Job difficulty. Difficult tasks are also typically more complex. Groups should be prepared to spend time researching and discussing a difficult and circuitous task in club to develop a shared foundational knowledge. This typically requires individual work outside of the grouping and frequent grouping meetings to share data.

- Number of possible solutions. There are usually multiple means to solve a problem or complete a task, only some problems have more potential solutions than others. Figuring out how to prepare a beach house for an budgeted hurricane is fairly circuitous and difficult, but there are all the same a limited number of things to do—for example, taping and boarding up windows; turning off h2o, electricity, and gas; trimming copse; and securing loose exterior objects. Other problems may be more than creatively based. For example, designing a new restaurant may entail using some standard solutions but could also entail many unlike types of innovation with layout and design.

- Group fellow member interest in trouble. When group members are interested in the problem, they will be more engaged with the trouble-solving procedure and invested in finding a quality solution. Groups with high interest in and knowledge virtually the trouble may want more freedom to develop and implement solutions, while groups with low interest may prefer a leader who provides structure and direction.

- Group familiarity with trouble. Some groups meet a problem regularly, while other problems are more than unique or unexpected. A family who has lived in hurricane alley for decades probably has a ameliorate thought of how to set up its house for a hurricane than does a family that just recently moved from the Midwest. Many groups that rely on funding have to revisit a upkeep every year, and in recent years, groups have had to get more than creative with budgets equally funding has been cut in most every sector. When grouping members aren't familiar with a trouble, they will need to practice background research on what similar groups take done and may also need to bring in outside experts.

- Demand for solution acceptance. In this step, groups must consider how many people the decision volition touch and how much "buy-in" from others the grouping needs in club for their solution to be successfully implemented. Some small groups take many stakeholders on whom the success of a solution depends. Other groups are answerable only to themselves. When a small grouping is planning on building a new park in a crowded neighborhood or implementing a new policy in a large concern, it can be very difficult to develop solutions that volition exist accepted past all. In such cases, groups will want to poll those who volition exist affected by the solution and may desire to do a pilot implementation to see how people react. Imposing an excellent solution that doesn't have buy-in from stakeholders can even so lead to failure.

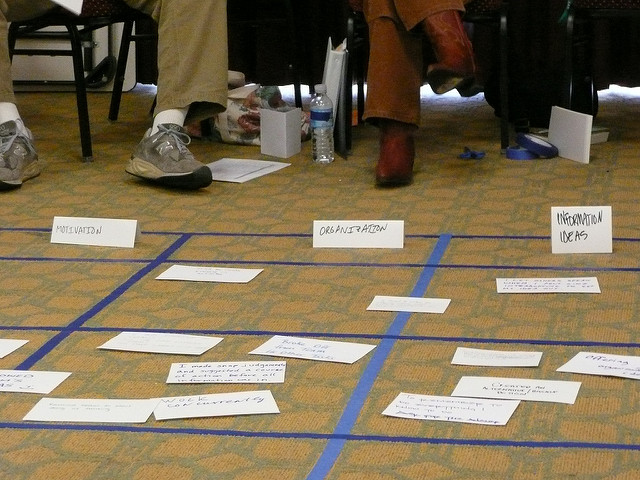

Group problem solving can be a confusing puzzle unless it is approached systematically.

Group Problem-Solving Process

There are several variations of like trouble-solving models based on US American scholar John Dewey's reflective thinking process (Bormann & Bormann, 1988). As you read through the steps in the process, think about how you can apply what we learned regarding the full general and specific elements of issues. Some of the following steps are straightforward, and they are things we would logically do when faced with a trouble. Even so, taking a deliberate and systematic approach to trouble solving has been shown to benefit group operation and performance. A deliberate arroyo is especially benign for groups that do not have an established history of working together and will just exist able to see occasionally. Although a group should attend to each pace of the procedure, group leaders or other group members who facilitate problem solving should be cautious not to dogmatically follow each element of the process or forcefulness a group along. Such a lack of flexibility could limit group member input and negatively affect the group's cohesion and climate.

Pace 1: Define the Problem

Define the problem past considering the three elements shared by every trouble: the current undesirable situation, the goal or more desirable state of affairs, and obstacles in the way (Adams & Galanes, 2009). At this stage, group members share what they know near the current situation, without proposing solutions or evaluating the information. Here are some good questions to ask during this stage: What is the current difficulty? How did we come to know that the difficulty exists? Who/what is involved? Why is it meaningful/urgent/important? What have the effects been and so far? What, if any, elements of the difficulty require clarification? At the end of this stage, the group should exist able to compose a single sentence that summarizes the problem called a trouble statement. Avoid diction in the trouble statement or question that hints at potential solutions. A pocket-sized group formed to investigate upstanding violations of urban center officials could use the following problem statement: "Our country does not currently take a mechanism for citizens to study suspected ethical violations by city officials."

Footstep two: Analyze the Trouble

During this step a group should analyze the problem and the group's human relationship to the problem. Whereas the outset pace involved exploring the "what" related to the problem, this footstep focuses on the "why." At this stage, group members tin can discuss the potential causes of the difficulty. Group members may besides want to begin setting out an agenda or timeline for the group's problem-solving process, looking forward to the other steps. To fully analyze the problem, the grouping can talk over the five mutual problem variables discussed before. Here are 2 examples of questions that the grouping formed to address ethics violations might ask: Why doesn't our city have an ethics reporting mechanism? Do cities of similar size accept such a mechanism? Once the trouble has been analyzed, the grouping can pose a problem question that will guide the grouping as it generates possible solutions. "How tin can citizens report suspected ethical violations of urban center officials and how will such reports exist processed and addressed?" As you lot tin see, the problem question is more complex than the problem argument, since the group has moved on to more than in-depth discussion of the trouble during step 2.

Step iii: Generate Possible Solutions

During this step, grouping members generate possible solutions to the problem. Again, solutions should not be evaluated at this signal, only proposed and clarified. The question should be what could we exercise to address this problem, not what should we do to address it. It is perfectly OK for a group member to question another person'southward idea past asking something like "What do you hateful?" or "Could you explicate your reasoning more than?" Discussions at this stage may reveal a need to return to previous steps to better define or more than fully analyze a problem. Since many problems are multifaceted, information technology is necessary for group members to generate solutions for each function of the problem separately, making sure to have multiple solutions for each role. Stopping the solution-generating process prematurely can pb to groupthink. For the trouble question previously posed, the group would need to generate solutions for all three parts of the problem included in the question. Possible solutions for the first function of the problem (How can citizens report ethical violations?) may include "online reporting system, e-mail, in-person, anonymously, on-the-tape," and so on. Possible solutions for the 2d office of the problem (How will reports be processed?) may include "daily by a newly appointed ethics officer, weekly by a nonpartisan nongovernment employee," and so on. Possible solutions for the third part of the problem (How will reports be addressed?) may include "by a newly appointed ethics commission, by the accused'south supervisor, past the city manager," and so on.

Stride 4: Evaluate Solutions

During this pace, solutions can exist critically evaluated based on their credibility, completeness, and worth. Once the potential solutions have been narrowed based on more obvious differences in relevance and/or merit, the group should analyze each solution based on its potential effects—especially negative furnishings. Groups that are required to report the rationale for their conclusion or whose decisions may exist subject field to public scrutiny would exist wise to make a set list of criteria for evaluating each solution. Additionally, solutions tin be evaluated based on how well they fit with the grouping's charge and the abilities of the group. To do this, group members may ask, "Does this solution live up to the original purpose or mission of the group?" and "Can the solution actually be implemented with our current resources and connections?" and "How will this solution be supported, funded, enforced, and assessed?" Secondary tensions and substantive conflict, two concepts discussed before, emerge during this step of problem solving, and grouping members will need to employ constructive critical thinking and listening skills.

Decision making is part of the larger process of trouble solving and information technology plays a prominent role in this step. While there are several fairly similar models for problem solving, there are many varied decision-making techniques that groups tin can use. For example, to narrow the list of proposed solutions, grouping members may decide by majority vote, by weighing the pros and cons, or by discussing them until a consensus is reached. There are also more complex decision-making models like the "six hats method," which nosotros will discuss later. Once the final decision is reached, the group leader or facilitator should confirm that the group is in agreement. It may be beneficial to allow the group break for a while or even to filibuster the final decision until a later meeting to allow people time to evaluate it exterior of the grouping context.

Step v: Implement and Assess the Solution

Implementing the solution requires some advanced planning, and it should not be rushed unless the group is operating under strict fourth dimension restraints or delay may atomic number 82 to some kind of harm. Although some solutions can be implemented immediately, others may have days, months, or years. As was noted earlier, it may be beneficial for groups to poll those who will exist afflicted by the solution as to their stance of it or even to do a airplane pilot test to observe the effectiveness of the solution and how people react to information technology. Before implementation, groups should also determine how and when they would assess the effectiveness of the solution by asking, "How will we know if the solution is working or not?" Since solution assessment volition vary based on whether or not the group is disbanded, groups should as well consider the following questions: If the group disbands afterwards implementation, who will be responsible for assessing the solution? If the solution fails, volition the aforementioned group reconvene or will a new group be formed?

Once a solution has been reached and the group has the "green light" to implement it, it should proceed deliberately and charily, making sure to consider possible consequences and address them every bit needed.

Certain elements of the solution may need to be delegated out to various people within and outside the group. Group members may besides be assigned to implement a particular part of the solution based on their function in the decision making or because information technology connects to their surface area of expertise. Likewise, group members may be tasked with publicizing the solution or "selling" it to a particular group of stakeholders. Last, the grouping should consider its future. In some cases, the grouping will get to decide if information technology will stay together and continue working on other tasks or if it will disband. In other cases, outside forces determine the grouping'due south fate.

"Getting Competent"

Problem Solving and Group Presentations

Giving a grouping presentation requires that individual grouping members and the group every bit a whole solve many bug and make many decisions. Although having more than people involved in a presentation increases logistical difficulties and has the potential to create more conflict, a well-prepared and well-delivered group presentation can be more engaging and effective than a typical presentation. The principal problems facing a group giving a presentation are (one) dividing responsibilities, (2) coordinating schedules and time management, and (3) working out the logistics of the presentation commitment.

In terms of dividing responsibilities, assigning individual piece of work at the first meeting and so trying to fit it all together before the presentation (which is what many higher students do when faced with a group project) is not the recommended method. Integrating content and visual aids created by several different people into a seamless last production takes fourth dimension and try, and the person "stuck" with this job at the cease usually ends up developing some resentment toward his or her group members. While it'southward OK for grouping members to do piece of work independently outside of grouping meetings, spend time working together to help set upwardly some standards for content and formatting expectations that will help make later integration of work easier. Taking the fourth dimension to consummate 1 role of the presentation together tin can help set those standards for later individual work. Talk over the roles that various grouping members will play openly so at that place isn't role confusion. There could be one signal person for keeping runway of the group's progress and schedule, one point person for communication, one indicate person for content integration, 1 point person for visual aids, and then on. Each person shouldn't do all that work on his or her own but assist focus the group's attention on his or her specific area during grouping meetings (Stanton, 2009).

Scheduling group meetings is ane of the most challenging problems groups face, given people'due south busy lives. From the beginning, it should be clearly communicated that the group needs to spend considerable time in face-to-face meetings, and group members should know that they may have to make an occasional sacrifice to nourish. Especially important is the commitment to scheduling time to rehearse the presentation. Consider creating a contract of group guidelines that includes expectations for coming together omnipresence to increase grouping members' delivery.

Grouping presentations require members to navigate many logistics of their presentation. While it may exist easier for a group to assign each member to create a five-infinitesimal segment and so transition from one person to the side by side, this is definitely non the most engaging method. Creating a chief presentation and then assigning individual speakers creates a more fluid and dynamic presentation and allows everyone to become familiar with the content, which can aid if a person doesn't show upwardly to present and during the question-and-answer section. Once the content of the presentation is consummate, figure out introductions, transitions, visual aids, and the use of time and space (Stanton, 2012). In terms of introductions, effigy out if one person volition introduce all the speakers at the beginning, if speakers will innovate themselves at the beginning, or if introductions will occur equally the presentation progresses. In terms of transitions, make sure each person has included in his or her speaking notes when presentation duties switch from one person to the next. Visual aids have the potential to cause hiccups in a group presentation if they aren't fluidly integrated. Practicing with visual aids and having ane person control them may help prevent this. Know how long your presentation is and know how you're going to employ the space. Presenters should know how long the whole presentation should be and how long each of their segments should be and so that anybody can share the responsibility of keeping time. Also consider the size and layout of the presentation space. You lot don't want presenters huddled in a corner until it's their turn to speak or trapped behind furniture when their turn comes effectually.

- Of the three main issues facing group presenters, which do you call back is the most challenging and why?

- Why practice you remember people tasked with a group presentation (especially students) adopt to divide the parts up and have members work on them independently before coming back together and integrating each function? What issues emerge from this method? In what ways might developing a master presentation and so assigning parts to different speakers exist better than the more divided method? What are the drawbacks to the principal presentation method?

Determination Making in Groups

Nosotros all engage in personal determination making daily, and we all know that some decisions are more difficult than others. When we make decisions in groups, we face some challenges that we practice non face in our personal decision making, but nosotros also stand to do good from some advantages of grouping decision making (Napier & Gershenfeld, 2004). Group decision making can appear fair and democratic merely really but be a gesture that covers up the fact that certain grouping members or the group leader take already decided. Group decision making also takes more fourth dimension than private decisions and can exist burdensome if some grouping members do not exercise their assigned work, divert the group with self-centered or unproductive role behaviors, or miss meetings. Conversely, though, grouping decisions are often more informed, since all group members develop a shared understanding of a problem through discussion and debate. The shared understanding may likewise be more circuitous and deep than what an individual would develop, considering the group members are exposed to a multifariousness of viewpoints that can augment their ain perspectives. Group decisions besides benefit from synergy, ane of the key advantages of group advice that nosotros discussed before. Near groups practise non employ a specific method of decision making, perhaps thinking that they'll work things out as they go. This can pb to unequal participation, social loafing, premature decisions, prolonged discussion, and a host of other negative consequences. So in this department we will larn some practices that will prepare u.s. for adept decision making and some specific techniques we can use to aid us reach a final decision.

Brainstorming before Determination Making

Before groups tin can make a decision, they need to generate possible solutions to their trouble. The almost commonly used method is brainstorming, although near people don't follow the recommended steps of brainstorming. As you'll recollect, brainstorming refers to the quick generation of ideas free of evaluation. The originator of the term brainstorming said the following four rules must be followed for the technique to exist constructive (Osborn, 1959):

- Evaluation of ideas is forbidden.

- Wild and crazy ideas are encouraged.

- Quantity of ideas, non quality, is the goal.

- New combinations of ideas presented are encouraged.

To make brainstorming more of a decision-making method rather than an thought-generating method, group communication scholars take suggested additional steps that precede and follow brainstorming (Cragan & Wright, 1991).

- Practice a warm-up brainstorming session. Some people are more apprehensive about publicly communicating their ideas than others are, and a warm-up session can assistance ease apprehension and prime number group members for task-related thought generation. The warm-up tin be initiated by anyone in the grouping and should only proceed for a few minutes. To get things started, a person could ask, "If our group formed a band, what would we exist called?" or "What other purposes could a mailbox serve?" In the previous examples, the first warm up gets the group's more than abstract artistic juices flowing, while the 2nd focuses more on applied and concrete ideas.

- Practise the bodily brainstorming session. This session shouldn't last more than thirty minutes and should follow the four rules of brainstorming mentioned previously. To ensure that the 4th dominion is realized, the facilitator could encourage people to piggyback off each other's ideas.

- Eliminate duplicate ideas. After the brainstorming session is over, grouping members can eliminate (without evaluating) ideas that are the same or very similar.

- Analyze, organize, and evaluate ideas. Earlier evaluation, meet if any ideas need clarification. Then try to theme or group ideas together in some orderly way. Since "wild and crazy" ideas are encouraged, some suggestions may need clarification. If it becomes clear that there isn't really a foundation to an idea and that information technology is too vague or abstract and can't be antiseptic, it may be eliminated. As a caution though, it may be wise to non throw out off-the-wall ideas that are hard to categorize and to instead put them in a miscellaneous or "wild and crazy" category.

Discussion earlier Conclusion Making

The nominal group technique guides determination making through a four-step procedure that includes idea generation and evaluation and seeks to elicit equal contributions from all group members (Delbecq & Ven de Ven, 1971). This method is useful because the procedure involves all group members systematically, which fixes the trouble of uneven participation during discussions. Since everyone contributes to the give-and-take, this method tin too help reduce instances of social loafing. To utilize the nominal group technique, do the post-obit:

- Silently and individually list ideas.

- Create a primary list of ideas.

- Clarify ideas as needed.

- Take a hole-and-corner vote to rank grouping members' acceptance of ideas.

During the first footstep, have group members piece of work quietly, in the aforementioned space, to write downward every idea they have to address the task or problem they face. This shouldn't take more than than twenty minutes. Whoever is facilitating the word should remind grouping members to use brainstorming techniques, which means they shouldn't evaluate ideas every bit they are generated. Ask group members to remain silent once they've finished their listing so they practice not distract others.

During the second stride, the facilitator goes around the grouping in a consistent club asking each person to share one thought at a fourth dimension. As the idea is shared, the facilitator records it on a primary list that everyone can see. Keep rails of how many times each idea comes up, as that could exist an idea that warrants more discussion. Continue this process until all the ideas take been shared. As a note to facilitators, some grouping members may begin to edit their list or cocky-censor when asked to provide one of their ideas. To limit a person's apprehension with sharing his or her ideas and to ensure that each idea is shared, I have asked group members to commutation lists with someone else so they tin share ideas from the list they receive without fear of beingness personally judged.

During step three, the facilitator should note that grouping members can at present ask for clarification on ideas on the master list. Do not allow this discussion stray into evaluation of ideas. To help avert an unnecessarily long discussion, it may be useful to go from one person to the next to ask which ideas demand clarifying and so go to the originator(s) of the thought in question for clarification.

During the fourth step, members use a voting ballot to rank the acceptability of the ideas on the primary listing. If the list is long, you may ask group members to rank only their meridian five or so choices. The facilitator then takes up the clandestine ballots and reviews them in a random order, noting the rankings of each idea. Ideally, the highest ranked idea can then be discussed and decided on. The nominal grouping technique does not conduct a group all the manner through to the point of decision; rather, it sets the group upwards for a roundtable word or use of some other method to evaluate the merits of the summit ideas.

Specific Conclusion-Making Techniques

Some determination-making techniques involve determining a class of action based on the level of agreement amongst the grouping members. These methods include bulk, proficient, authority, and consensus dominion. Tabular array xiv.1 "Pros and Cons of Agreement-Based Decision-making Techniques" reviews the pros and cons of each of these methods.

Majority rule is a simple method of decision making based on voting. In most cases a majority is considered one-half plus one.

Becky McCray – Voting – CC BY-NC-ND two.0.

Bulk dominion is a commonly used decision-making technique in which a majority (one-half plus one) must concord before a determination is made. A show-of-easily vote, a newspaper election, or an electronic voting organization tin determine the majority choice. Many decision-making bodies, including the The states Firm of Representatives, Senate, and Supreme Court, use majority rule to make decisions, which shows that it is ofttimes associated with democratic decision making, since each person gets one vote and each vote counts every bit. Of course, other individuals and mediated messages tin influence a person's vote, but since the voting ability is spread out over all grouping members, it is not easy for one person or party to have control of the decision-making process. In some cases—for example, to override a presidential veto or to meliorate the constitution—a super majority of two-thirds may be required to make a decision.

Minority rule is a controlling technique in which a designated authority or expert has concluding say over a decision and may or may non consider the input of other group members. When a designated good makes a decision past minority rule, there may be buy-in from others in the group, particularly if the members of the group didn't take relevant knowledge or expertise. When a designated authority makes decisions, buy-in will vary based on group members' level of respect for the authorization. For example, decisions made past an elected potency may be more accepted by those who elected him or her than by those who didn't. As with majority dominion, this technique can be time saving. Dissimilar bulk dominion, one person or party can have command over the decision-making procedure. This type of conclusion making is more similar to that used by monarchs and dictators. An obvious negative event of this method is that the needs or wants of one person can override the needs and wants of the bulk. A minority deciding for the majority has led to negative consequences throughout history. The white Afrikaner minority that ruled South Africa for decades instituted apartheid, which was a organization of racial segregation that disenfranchised and oppressed the majority population. The quality of the decision and its fairness really depends on the designated expert or authority.

Consensus dominion is a controlling technique in which all members of the group must agree on the same decision. On rare occasions, a decision may exist ideal for all group members, which tin lead to unanimous understanding without further debate and discussion. Although this can be positive, exist cautious that this isn't a sign of groupthink. More typically, consensus is reached merely after lengthy give-and-take. On the plus side, consensus oft leads to high-quality decisions due to the time and effort it takes to go everyone in agreement. Group members are also more than likely to be committed to the decision because of their investment in reaching it. On the negative side, the ultimate decision is often one that all group members tin live with but not 1 that's platonic for all members. Additionally, the process of arriving at consensus also includes disharmonize, as people debate ideas and negotiate the interpersonal tensions that may result.

Table 14.1 Pros and Cons of Agreement-Based Controlling Techniques

| Controlling Technique | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Majority rule |

|

|

| Minority rule by practiced |

|

|

| Minority rule by authority |

|

|

| Consensus rule |

|

|

"Getting Disquisitional"

Six Hats Method of Decision Making

Edward de Bono developed the Vi Hats method of thinking in the late 1980s, and it has since become a regular feature in decision-making grooming in business and professional contexts (de Bono, 1985). The method'south popularity lies in its ability to assistance people get out of habitual means of thinking and to allow group members to play dissimilar roles and meet a trouble or decision from multiple points of view. The bones idea is that each of the half dozen hats represents a different manner of thinking, and when we figuratively switch hats, we switch the style nosotros recollect. The hats and their manner of thinking are equally follows:

- White lid. Objective—focuses on seeking information such as information and facts and and so processes that information in a neutral manner.

- Ruddy lid. Emotional—uses intuition, gut reactions, and feelings to judge information and suggestions.

- Black hat. Negative—focuses on potential risks, points out possibilities for failure, and evaluates information charily and defensively.

- Yellow hat. Positive—is optimistic about suggestions and future outcomes, gives effective and positive feedback, points out benefits and advantages.

- Dark-green lid. Creative—tries to generate new ideas and solutions, thinks "exterior the box."

- Blue chapeau. Philosophical—uses metacommunication to organize and reverberate on the thinking and communication taking place in the group, facilitates who wears what hat and when group members alter hats.

Specific sequences or combinations of hats can exist used to encourage strategic thinking. For instance, the group leader may start off wearing the Bluish Hat and suggest that the group start their conclusion-making procedure with some "White Hat thinking" in gild to procedure through facts and other available data. During this stage, the grouping could also procedure through what other groups have washed when faced with a like problem. And so the leader could begin an evaluation sequence starting with two minutes of "Yellow Hat thinking" to identify potential positive outcomes, then "Black Lid thinking" to allow group members to limited reservations nearly ideas and point out potential bug, then "Scarlet Hat thinking" to get people's gut reactions to the previous give-and-take, and then "Light-green Lid thinking" to identify other possible solutions that are more tailored to the grouping'due south situation or completely new approaches. At the terminate of a sequence, the Blue Hat would want to summarize what was said and brainstorm a new sequence. To successfully apply this method, the person wearing the Bluish Hat should be familiar with unlike sequences and plan some of the thinking patterns alee of time based on the trouble and the group members. Each circular of thinking should be limited to a certain time frame (two to five minutes) to proceed the word moving.

- This conclusion-making method has been praised because it allows group members to "switch gears" in their thinking and allows for part playing, which lets people express ideas more freely. How can this aid enhance disquisitional thinking? Which combination of hats practice you call up would be best for a critical thinking sequence?

- What combinations of hats might be useful if the leader wanted to break the larger group up into pairs and why? For case, what kind of thinking would result from putting Yellow and Cherry-red together, Blackness and White together, or Red and White together, so on?

- Based on your preferred ways of thinking and your personality, which hat would be the all-time fit for you? Which would exist the most challenging? Why?

Influences on Decision Making

Many factors influence the conclusion-making process. For example, how might a grouping'south independence or access to resources impact the decisions they make? What potential advantages and disadvantages come with decisions fabricated by groups that are more or less similar in terms of personality and cultural identities? In this department, nosotros will explore how situational, personality, and cultural influences affect conclusion making in groups.

Situational Influences on Decision Making

A group's situational context affects decision making. One key situational element is the degree of liberty that the grouping has to brand its own decisions, secure its ain resource, and initiate its own actions. Some groups have to become through multiple approving processes earlier they can do anything, while others are self-directed, self-governing, and self-sustaining. Another situational influence is incertitude. In general, groups deal with more incertitude in decision making than do individuals considering of the increased number of variables that comes with calculation more than people to a situation. Individual group members can't know what other group members are thinking, whether or not they are doing their work, and how committed they are to the group. So the size of a grouping is a powerful situational influence, as information technology adds to incertitude and complicates communication.

Access to data also influences a group. Commencement, the nature of the grouping'south chore or problem affects its power to get data. Group members tin can more than easily brand decisions nigh a trouble when other groups take similarly experienced it. Even if the problem is complex and serious, the group can learn from other situations and use what it learns. Second, the group must have admission to flows of information. Access to archives, electronic databases, and individuals with relevant experience is necessary to obtain any relevant information most like problems or to exercise research on a new or unique trouble. In this regard, group members' formal and information network connections also become important situational influences.

The urgency of a conclusion tin can accept a major influence on the decision-making procedure. As a situation becomes more urgent, it requires more specific decision-making methods and types of advice.

Judith E. Bell – Urgent – CC Past-SA 2.0.

The origin and urgency of a problem are also situational factors that influence decision making. In terms of origin, problems usually occur in ane of four ways:

- Something goes wrong. Grouping members must decide how to set up or stop something. Example—a firehouse coiffure finds out that half of the edifice is contaminated with mold and must exist closed down.

- Expectations modify or increase. Grouping members must innovate more efficient or effective ways of doing something. Example—a firehouse crew finds out that the commune they are responsible for is being expanded.

- Something goes wrong and expectations modify or increase. Group members must fix/terminate and go more than efficient/effective. Case—the firehouse crew has to close half the building and must start responding to more calls due to the expanding district.

- The problem existed from the outset. Group members must go back to the origins of the situation and walk through and analyze the steps again to determine what tin be done differently. Example—a firehouse crew has consistently had to work with minimal resources in terms of edifice space and firefighting tools.

In each of the cases, the need for a determination may be more or less urgent depending on how badly something is going wrong, how high the expectations take been raised, or the caste to which people are fed upwardly with a cleaved system. Decisions must be made in situations ranging from crunch level to mundane.

Personality Influences on Determination Making

A long-studied typology of value orientations that touch decision making consists of the post-obit types of determination maker: the economic, the artful, the theoretical, the social, the political, and the religious (Spranger, 1928).

- The economic decision maker makes decisions based on what is practical and useful.

- The aesthetic decision maker makes decisions based on form and harmony, desiring a solution that is elegant and in sync with the environment.

- The theoretical decision maker wants to discover the truth through rationality.

- The social decision maker emphasizes the personal impact of a decision and sympathizes with those who may be afflicted by information technology.

- The political decision maker is interested in power and influence and views people and/or holding equally divided into groups that have different value.

- The religious decision maker seeks to identify with a larger purpose, works to unify others under that goal, and commits to a viewpoint, often denying one side and beingness dedicated to the other.

In the The states, economic, political, and theoretical conclusion making tend to be more prevalent conclusion-making orientations, which probable corresponds to the individualistic cultural orientation with its accent on competition and efficiency. But situational context, every bit we discussed before, can also influence our decision making.

Personality affects decision making. For example, "economic" decision makers decide based on what is practical and useful.

The personalities of group members, specially leaders and other active members, impact the climate of the group. Group member personalities tin be categorized based on where they fall on a continuum anchored past the following descriptors: dominant/submissive, friendly/unfriendly, and instrumental/emotional (Cragan & Wright, 1999). The more grouping members there are in whatever extreme of these categories, the more likely that the grouping climate will also shift to resemble those characteristics.

- Dominant versus submissive. Group members that are more than dominant deed more than independently and direct, initiate conversations, take up more than space, make more direct eye contact, seek leadership positions, and take control over decision-making processes. More submissive members are reserved, contribute to the grouping only when asked to, avoid eye contact, and leave their personal needs and thoughts unvoiced or give into the suggestions of others.

- Friendly versus unfriendly. Group members on the friendly side of the continuum observe a residual between talking and listening, don't endeavour to win at the expense of other grouping members, are flexible but not weak, and value democratic decision making. Unfriendly grouping members are disagreeable, indifferent, withdrawn, and selfish, which leads them to either not invest in decision making or direct it in their ain interest rather than in the interest of the group.

- Instrumental versus emotional. Instrumental group members are emotionally neutral, objective, analytical, job-oriented, and committed followers, which leads them to piece of work hard and contribute to the group's decision making as long as it is orderly and follows agreed-on rules. Emotional group members are artistic, playful, contained, unpredictable, and expressive, which leads them to make rash decisions, resist group norms or decision-making structures, and switch often from relational to task focus.

Cultural Context and Decision Making

Just like neighborhoods, schools, and countries, pocket-size groups vary in terms of their degree of similarity and departure. Demographic changes in the United States and increases in engineering science that can bring dissimilar people together make information technology more likely that nosotros will be interacting in more and more heterogeneous groups (Allen, 2011). Some small groups are more homogenous, meaning the members are more similar, and some are more than heterogeneous, meaning the members are more different. Diversity and difference within groups has advantages and disadvantages. In terms of advantages, inquiry finds that, in general, groups that are culturally heterogeneous accept meliorate overall performance than more homogenous groups (Haslett & Ruebush, 1999). Additionally, when grouping members have fourth dimension to get to know each other and competently communicate across their differences, the advantages of diversity include better conclusion making due to unlike perspectives (Thomas, 1999). Unfortunately, groups oft operate under time constraints and other pressures that brand the possibility for intercultural dialogue and agreement hard. The main disadvantage of heterogeneous groups is the possibility for conflict, but given that all groups experience conflict, this isn't solely due to the presence of diversity. We will now look more specifically at how some of the cultural value orientations we've learned about already in this book tin can play out in groups with international diversity and how domestic diversity in terms of demographics tin likewise influence grouping decision making.

International Diverseness in Grouping Interactions

Cultural value orientations such as individualism/collectivism, power altitude, and loftier-/low-context communication styles all manifest on a continuum of advice behaviors and can influence group decision making. Group members from individualistic cultures are more probable to value task-oriented, efficient, and directly communication. This could manifest in behaviors such as dividing upward tasks into private projects before collaboration begins then openly debating ideas during discussion and decision making. Additionally, people from cultures that value individualism are more likely to openly limited dissent from a decision, essentially expressing their disagreement with the group. Group members from collectivistic cultures are more likely to value relationships over the task at hand. Because of this, they besides tend to value conformity and face-saving (often indirect) advice. This could manifest in behaviors such as establishing norms that include periods of socializing to build relationships before task-oriented communication similar negotiations begin or norms that limit public disagreement in favor of more indirect communication that doesn't challenge the face of other group members or the group's leader. In a group composed of people from a collectivistic culture, each member would likely play harmonizing roles, looking for signs of disharmonize and resolving them before they become public.

Power altitude can also affect grouping interactions. Some cultures rank higher on ability-distance scales, meaning they value hierarchy, make decisions based on status, and believe that people have a set place in society that is fairly unchangeable. Group members from high-power-distance cultures would likely appreciate a potent designated leader who exhibits a more directive leadership manner and prefer groups in which members have clear and assigned roles. In a group that is homogenous in terms of having a high-power-distance orientation, members with higher condition would exist able to openly provide data, and those with lower status may not provide data unless a higher status member explicitly seeks it from them. Low-power-altitude cultures practice not place as much value and meaning on status and believe that all group members can participate in decision making. Grouping members from low-power-distance cultures would probable freely speak their mind during a group coming together and prefer a participative leadership style.

How much significant is conveyed through the context surrounding verbal communication tin also bear on group communication. Some cultures accept a high-context communication style in which much of the meaning in an interaction is conveyed through context such every bit nonverbal cues and silence. Group members from high-context cultures may avoid saying something directly, assuming that other group members will understand the intended meaning even if the bulletin is indirect. So if someone disagrees with a proposed form of activeness, he or she may say, "Let's talk over this tomorrow," and mean, "I don't call up we should do this." Such indirect advice is also a face up-saving strategy that is common in collectivistic cultures. Other cultures have a depression-context communication fashion that places more than importance on the meaning conveyed through words than through context or nonverbal cues. Group members from low-context cultures often say what they mean and mean what they say. For case, if someone doesn't like an idea, they might say, "I think we should consider more options. This one doesn't seem similar the all-time we tin do."

In whatever of these cases, an individual from one civilization operating in a grouping with people of a different cultural orientation could adapt to the expectations of the host culture, peculiarly if that person possesses a high caste of intercultural communication competence (ICC). Additionally, people with high ICC tin can also adapt to a group member with a unlike cultural orientation than the host culture. Even though these cultural orientations connect to values that affect our communication in fairly consistent ways, individuals may showroom dissimilar communication behaviors depending on their ain private communication mode and the state of affairs.

Domestic Variety and Grouping Communication

While it is condign more likely that we will interact in pocket-size groups with international diversity, we are guaranteed to interact in groups that are various in terms of the cultural identities found within a single land or the subcultures constitute inside a larger cultural group.

Gender stereotypes sometimes influence the roles that people play within a grouping. For example, the stereotype that women are more than nurturing than men may lead group members (both male person and female) to await that women volition play the role of supporters or harmonizers within the group. Since women have primarily performed secretarial work since the 1900s, it may also be expected that women volition play the part of recorder. In both of these cases, stereotypical notions of gender place women in roles that are typically not as valued in group advice. The opposite is true for men. In terms of leadership, despite notable exceptions, research shows that men fill up an overwhelmingly disproportionate amount of leadership positions. We are socialized to encounter certain behaviors past men as indicative of leadership abilities, even though they may not be. For example, men are often perceived to contribute more than to a group because they tend to speak first when asked a question or to make full a silence and are perceived to talk more nearly chore-related matters than relationally oriented matters. Both of these tendencies create a perception that men are more engaged with the job. Men are too socialized to be more competitive and cocky-congratulatory, pregnant that their communication may exist seen every bit dedicated and their behaviors seen equally powerful, and that when their work isn't noticed they will be more likely to brand it known to the grouping rather than take silent credit. Even though we know that the relational elements of a group are crucial for success, fifty-fifty in high-operation teams, that work is non as valued in our society as the job-related piece of work.

Despite the fact that some communication patterns and behaviors related to our typical (and stereotypical) gender socialization impact how we interact in and grade perceptions of others in groups, the differences in group advice that used to be attributed to gender in early grouping communication research seem to exist diminishing. This is likely due to the changing organizational cultures from which much group work emerges, which take at present had more than sixty years to adapt to women in the workplace. It is also due to a more nuanced agreement of gender-based research, which doesn't take a stereotypical view from the beginning as many of the early male researchers did. Now, instead of biological sex activity existence assumed every bit a factor that creates inherent communication differences, grouping communication scholars see that men and women both exhibit a range of behaviors that are more or less feminine or masculine. It is these gendered behaviors, and not a person's gender, that seem to have more of an influence on perceptions of group communication. Interestingly, group interactions are still masculinist in that male person and female group members prefer a more masculine communication style for task leaders and that both males and females in this role are more likely to adapt to a more masculine advice mode. Conversely, men who take on social-emotional leadership behaviors adopt a more than feminine communication style. In curt, it seems that although masculine communication traits are more often associated with high condition positions in groups, both men and women adapt to this expectation and are evaluated similarly (Haslett & Ruebush, 1999).

Other demographic categories are also influential in grouping communication and decision making. In general, group members take an easier time communicating when they are more similar than dissimilar in terms of race and age. This ease of communication can make group work more than efficient, only the homogeneity may sacrifice some inventiveness. As we learned before, groups that are diverse (due east.g., they accept members of different races and generations) benefit from the diverseness of perspectives in terms of the quality of decision making and creativity of output.

In terms of age, for the get-go fourth dimension since industrialization began, information technology is common to have iii generations of people (and sometimes four) working side by side in an organizational setting. Although iv generations often worked together in early factories, they were segregated based on their age group, and a hierarchy existed with older workers at the top and younger workers at the bottom. Today, however, generations collaborate regularly, and it is not uncommon for an older person to accept a leader or supervisor who is younger than him or her (Allen, 2011). The electric current generations in the U.s. workplace and consequently in work-based groups include the following:

- The Silent Generation. Born between 1925 and 1942, currently in their midsixties to mideighties, this is the smallest generation in the workforce right at present, every bit many take retired or left for other reasons. This generation includes people who were born during the Bully Low or the early role of Globe War Ii, many of whom later fought in the Korean War (Clarke, 1970).

- The Baby Boomers. Built-in betwixt 1946 and 1964, currently in their late forties to midsixties, this is the largest generation in the workforce right at present. Baby boomers are the most populous generation born in US history, and they are working longer than previous generations, which ways they will remain the predominant force in organizations for ten to twenty more than years.

- Generation X. Born between 1965 and 1981, currently in their early thirties to midforties, this generation was the offset to meet engineering science similar cell phones and the Cyberspace make its way into classrooms and our daily lives. Compared to previous generations, "Gen-Xers" are more than diverse in terms of race, religious behavior, and sexual orientation and as well take a greater appreciation for and understanding of variety.

- Generation Y. Built-in between 1982 and 2000, "Millennials" as they are also called are currently in their late teens upwardly to most thirty years old. This generation is not equally likely to think a time without technology such as computers and cell phones. They are just starting to enter into the workforce and accept been greatly affected by the economic crisis of the late 2000s, experiencing significantly loftier unemployment rates.

The benefits and challenges that come with diversity of group members are important to consider. Since we will all piece of work in various groups, we should be prepared to accost potential challenges in order to reap the benefits. Various groups may exist wise to coordinate social interactions outside of group time in order to find common ground that tin help facilitate interaction and increment group cohesion. We should be sensitive but not allow sensitivity create fear of "doing something wrong" that then prevents united states from having meaningful interactions. Reviewing Chapter 8 "Civilization and Advice" will requite you useful knowledge to help you navigate both international and domestic diversity and increase your communication competence in small groups and elsewhere.

Key Takeaways

- Every problem has common components: an undesirable state of affairs, a desired situation, and obstacles betwixt the undesirable and desirable situations. Every trouble also has a set up of characteristics that vary among problems, including task difficulty, number of possible solutions, group member interest in the problem, group familiarity with the problem, and the need for solution acceptance.

-

The grouping problem-solving process has five steps:

- Define the problem past creating a trouble statement that summarizes it.

- Analyze the problem and create a trouble question that can guide solution generation.

- Generate possible solutions. Possible solutions should exist offered and listed without stopping to evaluate each one.

- Evaluate the solutions based on their credibility, completeness, and worth. Groups should also assess the potential furnishings of the narrowed list of solutions.

- Implement and assess the solution. Aside from enacting the solution, groups should make up one's mind how they volition know the solution is working or not.

- Before a group makes a decision, information technology should brainstorm possible solutions. Group communication scholars suggest that groups (1) do a warm-up brainstorming session; (2) do an actual brainstorming session in which ideas are non evaluated, wild ideas are encouraged, quantity non quality of ideas is the goal, and new combinations of ideas are encouraged; (3) eliminate indistinguishable ideas; and (4) clarify, organize, and evaluate ideas. In order to guide the thought-generation process and invite equal participation from group members, the group may besides elect to employ the nominal grouping technique.

- Common controlling techniques include majority dominion, minority rule, and consensus rule. With majority rule, just a bulk, usually half plus one, must agree earlier a decision is made. With minority dominion, a designated authority or proficient has final say over a conclusion, and the input of group members may or may non exist invited or considered. With consensus dominion, all members of the group must agree on the same conclusion.

-

Several factors influence the decision-making process:

- Situational factors include the caste of freedom a grouping has to make its own decisions, the level of doubtfulness facing the grouping and its task, the size of the group, the group's access to information, and the origin and urgency of the problem.

- Personality influences on decision making include a person'south value orientation (economic, aesthetic, theoretical, political, or religious), and personality traits (ascendant/submissive, friendly/unfriendly, and instrumental/emotional).

- Cultural influences on decision making include the heterogeneity or homogeneity of the group makeup; cultural values and characteristics such as individualism/collectivism, ability distance, and loftier-/low-context communication styles; and gender and historic period differences.

Exercises

- In terms of situational influences on group problem solving, task difficulty, number of possible solutions, grouping interest in problem, group familiarity with problem, and need for solution acceptance are v key variables discussed in this affiliate. For each of the 2 post-obit scenarios, talk over how the situational context created by these variables might affect the group's advice climate and the way it goes most addressing its problem.

- Scenario 1. Task difficulty is high, number of possible solutions is loftier, group interest in problem is high, group familiarity with problem is low, and need for solution credence is high.

- Scenario two. Task difficulty is low, number of possible solutions is low, grouping interest in problem is low, group familiarity with problem is loftier, and demand for solution credence is low.

- Getting integrated: Certain determination-making techniques may work amend than others in academic, professional, personal, or civic contexts. For each of the following scenarios, identify the decision-making technique that you think would be all-time and explain why.

- Scenario 1: Academic. A professor asks his or her form to decide whether the concluding examination should be an in-course or take-dwelling test.

- Scenario 2: Professional person. A group of coworkers must make up one's mind which person from their section to nominate for a company-broad honor.

- Scenario 3: Personal. A family needs to determine how to split up the belongings and estate of a deceased family member who did not leave a will.

- Scenario 4: Civic. A local branch of a political party needs to decide what five primal issues it wants to include in the national party's platform.

- Group advice researchers have found that heterogeneous groups (composed of diverse members) take advantages over homogenous (more similar) groups. Discuss a group situation you have been in where diversity enhanced your and/or the group'south experience.

References

Adams, Chiliad., and Gloria Thou. Galanes, Communicating in Groups: Applications and Skills, 7th ed. (Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill, 2009), 220–21.

Allen, B. J., Difference Matters: Communicating Social Identity, 2nd ed. (Long Grove, IL: Waveland, 2011), 5.

Bormann, E. 1000., and Nancy C. Bormann, Constructive Small Grouping Communication, 4th ed. (Santa Rosa, CA: Burgess CA, 1988), 112–13.

Clarke, K., "The Silent Generation Revisited," Fourth dimension, June 29, 1970, 46.

Cragan, J. F., and David W. Wright, Communication in Small-scale Group Discussions: An Integrated Approach, 3rd ed. (St. Paul, MN: Due west Publishing, 1991), 77–78.

de Bono, E., Six Thinking Hats (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1985).

Delbecq, A. 50., and Andrew H. Ven de Ven, "A Group Process Model for Trouble Identification and Programme Planning," The Periodical of Applied Behavioral Scientific discipline vii, no. 4 (1971): 466–92.

Haslett, B. B., and Jenn Ruebush, "What Differences Exercise Individual Differences in Groups Brand?: The Effects of Individuals, Civilization, and Group Composition," in The Handbook of Grouping Communication Theory and Enquiry, ed. Lawrence R. Frey (Yard Oaks, CA: Sage, 1999), 133.

Napier, R. W., and Matti K. Gershenfeld, Groups: Theory and Experience, 7th ed. (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 2004), 292.

Osborn, A. F., Applied Imagination (New York: Charles Scribner'southward Sons, 1959).

Spranger, E., Types of Men (New York: Steckert, 1928).

Stanton, C., "How to Evangelize Group Presentations: The Unified Squad Approach," 6 Minutes Speaking and Presentation Skills, November 3, 2009, accessed Baronial 28, 2012, http://sixminutes.dlugan.com/group-presentations-unified-team-approach.

Thomas, D. C., "Cultural Diversity and Work Group Effectiveness: An Experimental Study," Journal of Cantankerous-Cultural Psychology xxx, no. 2 (1999): 242–63.

Source: https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication/chapter/14-3-problem-solving-and-decision-making-in-groups/

Posted by: kochmundint.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Solve A Word Problem Involving Free Throws, Two Point Field Goals And Three Point Field Goals"

Post a Comment